By Rochelle Davis

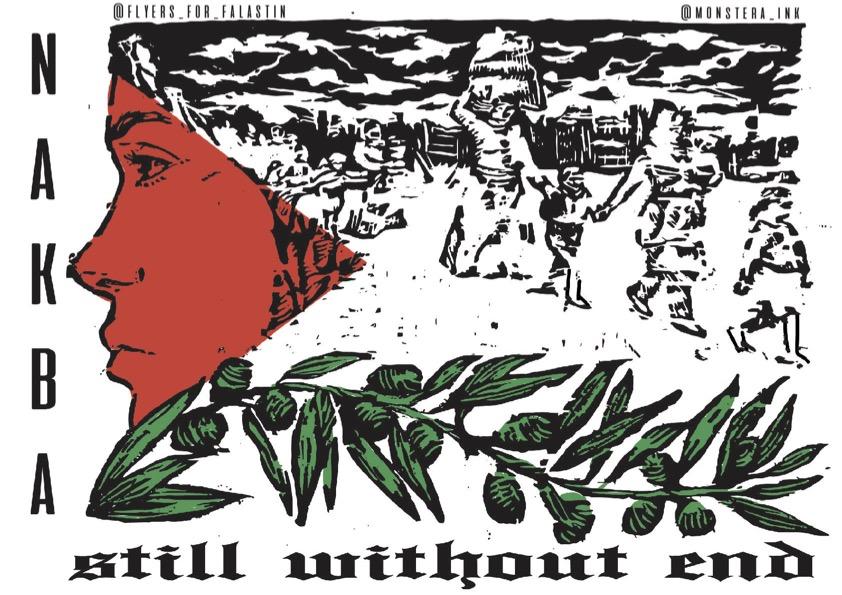

In my book, Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced (Stanford University Press, 2011), I explored how histories are constructed and told, and the power to narrate the past. I was keen to understand what sort of narratives became “history,” and in particular how known historical events are fleshed out, supplemented, clarified or undermined by individual and collective memories and experiences. Today we are witnessing the retelling and reassertion of the past, on the global stage, as Israel executes its genocidal violence on Gaza.

Palestinians are at a disadvantage in the struggle to create official historical narratives. Because Palestinians live in a number of different countries and have no state of their own, they have had little ability to hold on to records and documents, build archives, and maintain other material and structural sources that are used in the writing of history. They are without a state, do not sit as a state in the United Nations General Assembly, and until the post-1993 Oslo Accord creation of the Palestinian Authority, did not create their own school textbooks. Even when they have created archives, libraries, and institutions, they are subject to Israeli targeting and destruction. For example, in the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the Palestine Research Center was looted and all of the material was taken to Israel—documents, photographs, films—and later returned to the PLO in Algeria to an unknown fate. Among the targets of destruction in the 2002 Israeli re-invasion of the West Bank was the Ministry of Culture. In Gaza today, the term “scholasticide” is used to describe the destruction of every institution of higher education (twelve) and 80% of schools. In addition, the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) documented the damage to or destruction of “more than 200 of the 325 registered sites in Gaza.”

This repeated destruction of the institutions that Palestinians build to tell their history, transmit their culture, educate their children, and create their society is part of the attempt to eliminate and silence them. But Palestinians persevere. They write their histories in other ways. Collecting oral histories and the stories of the elders was and remains a hugely important part of Palestinian life. During my research, I spent a lot of time talking to Palestinians about where they learn their histories. In the early 2000s in refugee camps and urban neighborhoods in Damascus, Beirut, Tripoli, Ramallah, and Amman, Palestinians told me over and over that it was their grandparents, aunts, uncles and other family members who they turned to in order to learn history. My conclusion was that for many Palestinians, the past is held alive in the present through the people in their lives, their memories, and their stories.

These sources have provided rich material for different ways of writing history. What has emerged from research institutes, universities, communal organizations, and individuals’ collections and memories, are projects to tell those stories and histories from the perspectives of the people who lived. These projects include autobiographies, village memorial books, and oral history collections that exist on a popular level as expressions of individual, local, and communal understandings of the past. And more as people collect documents and make films, find old family photographs and document heritage practices, they have established museums, websites, and YouTube channels to preserve these histories.

Another part of the challenge Palestinians face in telling their histories is managing the framing or meaning of those histories. Take, for example, an event—a massacre—that happened in 1948. On April 9 of that year, more than a month before the creation of the state of Israel, at least 107 Palestinians in the small village of Deir Yassin were killed in an attack on the village by the Zionist Irgun and Stern Gang militias. The massacre was communicated with horror and fear on the radio (in Arabic), in newspapers, and from person to person. For Palestinians at the time, the killings served to frighten them as they imagined what would happen if the Zionist militias came to their own towns or villages. For many years, it formed a narrative node around which story of the Palestinian Nakba of 1948 and the creation of the Israeli state was told. In the 1980s, Birzeit University, a Palestinian university in the West Bank, wrote about Deir Yassin in their village book oral history series, documenting life before the massacre along with the names of those killed and displacement of the villagers.

Fifty years later, in 1998 the Zionist Organization of America published a report titled “Deir Yassin: History of a Lie.” In that study, the authors investigated primary and secondary sources to “clarify what really happened in Deir Yassin on that fateful day.” Despite using and praising the Birzeit book for its accuracy, the report authors unconvincingly concluded that “the Israeli judicial ruling in 1952, [was] an official recognition … that the battle was, in fact, a legitimate military operation against enemy armed forces,” and thus that the massacre was a lie. By changing the focus of the attention to be about representations of the event (massacre vs. military operation) rather than the events (the killing of men, women, and children), the report sought to point out the contradictions (of the largely secondary accounts) and de-legitimize any but their own interpretation of the past.

The Israeli government created the 2011 Nakba Law that authorizes the Minister of Finance to reduce funding to institutions that commemorate or acknowledge the displacement of more than half of the native Palestinian population and the destruction of their communities with the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. Israeli officials who have long denied “the Nakba” now threaten a “Gaza Nakba” (in the words of Israeli security cabinet member and Agriculture Minister Avi Dichter last November). This language both acknowledges that there was a Nakba in 1948 (violating their own 2011 law), as well as expressing the willingness to do it again and engage in war crimes in violation of the Geneva Conventions.

These examples show how Israeli officials and Zionist institutions justify violence and claim people’s deaths as part of the logic of war. Whether 1948 or 1998 or Gaza today, this logic of war is used to excuse the deaths of civilians who are made “killable” because the forces used against them are declared “legitimate military operations against enemy armed forces.” Same words, same targets, different wars. Palestinian deaths are being streamed to us live and yet, despite the over 35,000 Gazans who have been killed in the last 7 months, nothing has been done to stop it. In the past, Palestinians thought that no one listened to their stories; in the present, they know that people are listening but not doing anything about it. Or what they are doing doesn’t have the power (yet) to change most countries’ political and military support for Israel.

As we witness the destruction of Gaza – of life, of history, of the present – we are also witnessing the destruction of a future. Without schools and universities, without hospitals and clinics, without infrastructure, life as it was known becomes harder to imagine. How will history tell this story? Our new digital world has brought the destruction and suffering, the war crimes, to the screens in our pockets and purses. We are witnessing the destruction of what was, just as the world witnessed the destruction of Palestinian life in 1948. We can know, however, that Palestinians’ long reliance on their lived experiences is a source of history that forms a testimony of and testament to life.

Dr. Rochelle Davis is the CCAS Director of Graduate Studies, Associate Professor of Anthropology, and the Sultanate of Oman Chair.

This article was published in the Fall 2023-Spring 2024 issue of the CCAS Newsmagazine.